While historians disagree on some facts regarding Josefa Baca, there is no dispute that she was the owner of the large tract of land known as the settlement of Pajarito located south of Albuquerque. After six generations of continuous occupation, her descendents successfully petitioned for ownership of the land.

Much of the history of Josefa Baca’s life, including details of her upbringing and marriage, remains unconfirmed and clouded by contradictory reports. However, historians do not dispute that in the late 1700s, she became the owner of the large tract of land that developed into the town of Pajarito, south of Albuquerque.

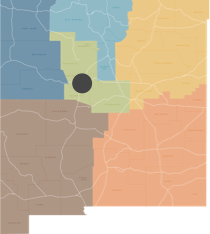

Josefa Baca was born around 1685 in El Paso del Norte to Manuel Baca and Maria de Salazar. By 1713, she had begun buying land, and by 1733, had acquired what was known as the “Sitio de San Ysidro de Pajarito,” a hacienda first described in 1643 as being owned by a priest at Isleta Pueblo. Based on the dimensions of the tract later upheld as a land grant, the boundaries of the land she acquired roughly stretched from the Rio Puerco east to the Rio Grande, south to what is now Los Padillas, and north to what is now Pajarito Road. It encompassed and was the nucleus of what is today the settlement of Pajarito, a southern suburb of Albuquerque. On her land, she had an 18-room hacienda, a chapel and sacristy.

The name Pajarito, which translates from Spanish to “little bird,” is possibly a reference to birds in the trees along the river, or an Indian surname. Spanish law allowed a woman to purchase and own land, but it is unknown how Josefa came into possession of her land.

As summarized by the Gutierrez-Hubbel House Museum: The village of Pajarito, or “Little Bird,” was not founded as a town so much as it “came into being.” It started as a cluster of small buildings surrounding the large family compound in the heart of Josefa Baca’s private estate. These were the homes of wage earners, peons, and servants who made their way by working for the Bacas. Like other agricultural villages owned by wealthy families, Pajarito’s fortunes were tied to the success of the Baca’s enterprises. In time, the family’s prosperity drew upper-class spouses for their children, and by the early 1800s, Gutierrez, Rubi, Sarracino, and Peña men had married into the family. Their nearby compounds added new generations of workers to the list of village residents.

According to her will, Baca died in 1746. Some of what historians know about her life has been discerned from her will—perhaps most importantly, that she was a person of means. As Carmen Espinosa explains in her review of clothing worn by the women of New Mexico in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: “Gowns and accessories listed [in wills] must not be considered typical of what the general public wore. The testators who made their wills evidently were individuals of means and rank, as one cannot testate if one has nothing to list.”

In her will, written on October 5, 1746, Josefa lists an inventory of 500 sheep, 100 goats, 2 horses, a musket, 2 bridles, 7 horse collars, a new cart, 4 whips, 2 axes, 3 hoes, “some old serge skirts, others new, three blouses, white skirts, stockings, shoes,” a bed with mattress, and other items. She owned her own brand. Her estate was valued at 2,822 pesos. Upon her death, she requested that two Indian women who had been her servants be set free and be given ten sheep each. Additionally, an image of Our Lady of Dolores was passed down through at least three generations.

Further, in the will she states: “I also declare that as a miserable and weak sinner I had six children who are Antonio Baca, Joseph Baca, Domingo, Manuel, Rosa and Isabel Baca, whom I brought up, fed and had married, and I have given them an equal part of my possessions.” The parentage of Josefa’s children is a mystery; it is not known if she was a wedded woman at her death or not, and the name of her children’s father(s) is similarly unknown.

After her death, six more generations continued to live on her original grant land, and the growth of the village of Pajarito centered around Josefa Baca’s estate. After New Mexico came under the rule of the United States, members of the extended Gutierrez family, all descended from Josefa Baca or having married into the family, petitioned the Surveyor General in 1877 claiming title to the land. Claiming that their ancestor, Clemente Gutierrez, held title to the Pajarito tract and, together with their ancestors, they held continuous, exclusive, uninterrupted, and peaceable possession of the land for 151 years, they made no mention of a “land grant” from a sovereign but they traced their title back to Josefa Baca’s 1746 will through a compilation of deeds, wills, leases, and other documents. They conceded that they did not know how Josefa Baca obtained the land or how long she had possessed it but they argued that they had been in continuous possession of the Pajarito tract from as far back as 1746 and had built houses and fences, planted orchards and vineyards, constructed an extensive irrigation system, and cultivated the lands since without anyone ever questioning their right or title to the tract.

The grant was finally confirmed on September 8, 1894.

Sources:

Interview: Flora Sanchez, docent, Gutiérrez-Hubbell House.

American National Biography. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Briseño, Elaine D. “Talk Explores Pajarito Family History.” Albuquerque Journal, Saturday, March 17, 2012.

Espinosa, Carmen. Shawls, Crinolines, Filigree: The Dress and Adornment of the Women of New Mexico, 1739 to 1900. El Paso: University of Texas at El Paso, n.d.

Julyan, Robert. Place Names of New Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998.

Lujan, Elaine Patricia. “The Pajarito Land Grant: A Contextual Analysis of Its Confirmation by the U.S. Government.” Natural Resources Journal, Vol. 48, Fall 2008.

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. “Hubbell, James Lawrence and Juliana Gutiérrez y Chaves House.”

Sisneros, Samuel. “Josefa Baca: Matriarch of Colonial Pajarito.” La Bandera, April 16, 2012.