Dona Elena Gallegos marker

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Karen Abraham, New Mexico Historic Women Marker Program

Doña Elena Gallegos

1690 - 1731

Bernalillo County

During the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, she fled New Mexico as an infant with her parents, Hispanic colonists. She returned in 1693 with two brothers and an uncle, was married in 1699 and widowed in 1711, when she became owner of the vast landholding near Albuquerque that has since borne her name.

Doña Elena Gallegos was the daughter of early seventeenth-century Hispanic colonists Antonio Gallegos and Catalina Baca. They fled New Mexico with their newborn daughter during the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. She returned as a young girl in 1693 with two brothers and an uncle. In 1699, she wed. In 1711, as a widow with a young child, she took ownership of a 70,000-acre parcel of land near Albuquerque, which she worked and lived on until her death in September of 1731. She successfully applied for and obtained her own livestock brand in 1712, quite possibly the first woman to do so.

While much of her young life is unknown, in 1699, Doña Elena Gallegos married Santiago Gurulé, a tattooed Frenchman 17 years her senior, who had changed his name after surviving the ill-fated 1684 La Salle Expedition, an unsuccessful attempt by France to establish a colony near the Gulf of Mexico on land then owned by Spain. The Hispanic form of his surname, Gurulé, is unique: Anyone with this name has roots in New Mexico.

In 1703, she gave birth to their son, Antonio. When her husband died eight years later, Gallegos, a widow with a young son, did not remarry, but following Spanish custom, returned to her maiden name. Gallegos acquired the grant that now bears her name the following year and spent the rest of her life living and working her land.

Permanent Spanish settlement of land east of what is now Albuquerque and extending to the foothills of the Sandia Mountains began with a grant of land to Captain Diego Montoya by Governor Diego de Vargas shortly after the Pueblo Revolt. The original grant was made in 1694, but was later re-issued in 1712 by Governor Joseph Chacón Medina Salazar y Villasenor. The date of the re-issued grant in 1712 coincides with the land’s conveyance by Montoya (or his son) to the widow of Santiago Gurulé, a woman named Elena Gallegos, from which the grant now takes its name.

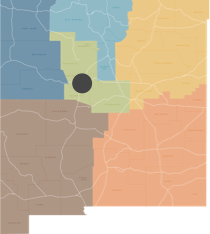

The boundaries of the approximately 70,000-acre grant extended from the Rio Grande to the crest of the Sandia Mountains, east to west, and from present-day Griegos Road in northwest Albuquerque to the Alameda Grant, south to north, land now largely populated by Albuquerque and surrounding villages. The extent of the grant was uncertain—some felt its eastern border was the foothills—until a nineteenth-century court interpreted the word “sierra” in the original document as the crest of the mountains. The adjudication helped make it possible to preserve part of the land grant as open space and provide a picnic area for the enjoyment of all.

While it’s unclear if Gallegos was given the land or purchased it, the Center for Land Grant Studies supports the latter: “Some have speculated that Diego Montoya left the land to Gallegos because the two were in love. However, this author is aware of no documentary evidence to either support or refute this claim. In fact, it is more likely that Montoya sold the land to Gallegos, instead of simply giving it to her. Furthermore, it was not uncommon for women, especially widows, to own property under Spanish colonial law. In fact, unlike English (and early U.S.) common law, under Spanish colonial law women retained ownership of property that they brought into a marriage. So it seems just as likely that Gallegos purchased the land as it does that Montoya would simply give away such a valuable tract to someone with no familial relationship to him. Indeed, Gallegos may have held a relatively high position in Hispano society, given that she registered her own brands with the Spanish colonial government and in these documents was referred to by the honorific ‘Doña.’”

According to an Albuquerque Journal article, she was the first woman to obtain her own livestock brand. In 1712, Gallegos wrote to the governor asking for permission to register her brand: “In order that I may brand my stock and horses so that no person may rob me, and with the condition that I and my children may take possession of any animals or stock branded with said brand … therefore, I ask your Excellency to make me a grant in the name of His Majesty of the said brand in order that I may use it for my own.”

Elena Gallegos died in 1731. Today, a portion of the Elena Gallegos Grant comprising the western foothills of the Sandias is used as an open space area and administered by the City of Albuquerque. It is popular with outdoor enthusiasts, and one trail includes a bird blind through which bird watchers can look for quail, bluebirds, flickers, robins, and other species.

Sources:

“Elena Gallegos Grant.” Center for Land Grant Studies, Guadalupita, NM, 2005.

Chávez, Fray Angélico. Origins of New Mexico Families: A Genealogy of the Spanish Colonial Period. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 1992.

Julyan, Robert. The Place Names of New Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998.

Liddell, Judy. Birding Hot Spots of Central New Mexico. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2011.

Piper, Jane. “Land Grant Links Past and Present,” Albuquerque Outlook, March 31, 1982.

Simmons, Marc. Albuquerque, a Narrative History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1982.

Jadrnak, Jackie. “Open Space is Treasured Legacy of Elena Gallegos.” Albuquerque Journal,

https://www.abqjournal.com/1450484/open-space-is-treasured-legacy-of-elena-gallegos.html